Africa’s borders are one of Pan-Africanism’s foundational obsessions. Are they ours, or Europe’s? Do we keep them, or erase them? Did we ever have our own?

Since just before the February decision by the Rwandan government to prevent access to its side of the border with Uganda, we have witnessed a shadowy quarrel between the presidencies of the two countries conducted in shorthand. The border closure was the first openly physical expression of this private argument. Since then, the language has become more robust, and the actions more direct, and even deadly.

With that act, Pan-Africanism came up against the realities of the European-designed political power upon which its member states rest. Perhaps, it will finally now look for an answer to its foundational riddle.

Some background may help here.

Yoweri Museveni, first as anti-Amin rebel activist, and later President of Uganda due to the bush exertions of his National Resistance Army (NRA), was seen –and saw himself – as the embodiment of the Pan-African ideal. Among his victorious soldiers were not insignificant numbers of refugees from Rwanda, some of whom had joined his crusade as far back as the days of General Idi Amin (1971-1979).

Museveni’s embrace, and even promotion to high office, of these excluded Africans was seen as real pan-Africanism in action. Paul Kagame was Uganda’s Deputy Director of Military Intelligence, and Major Fred Rwigyema (who died and was replaced by Kagame as the head of the Rwanda Patriotic Front [RPF]) was the Deputy Minister for Defence.

All this was celebrated, not least by the then luminaires of the attempted revival of the global Pan-Africanist movement led by the magnificently deluded Nigerian activist Tajudeen Abdul-Raheem, who went on to hold what was to be a major re-organisational 1994 conference in Kampala, which was gifted with a permanent secretariat afterwards.

Finally, the notion was cemented by the generous assistance Museveni’s NRA lent to the RPF invasion of Rwanda. In fact, the array of names of the Rwandan personalities (some now deceased) now quarreling among themselves contained a few alumni of Uganda’s Makerere University, as well as former employees of the Ugandan government. During broadcasts, if it were not for the bloodletting, it would be almost amusing watching them dispute in their Ugandan-accented English.

The genesis of the current stand-off

After the RPF victory in Kigali, one would have thought that the Pan-African flower had now bloomed. The RPF was viewed as part of the NRA but under a more focused leadership of the austere-looking disciplinarian Paul Kagame, with none of the shortcomings NRA have so venally displayed once in power.

The current stand-off is, therefore, a culminated development in a political history reaching back over four decades, which has come to define how a generation or two understand politics, war and regional diplomacy. The details of all the attendant schemes, betrayals and illegitimate victories, are theirs. The implications, however, belong to all of us. If these two peas-in-a-pod cannot get on, then who in the region will?

After the RPF victory in Kigali, one would have thought that the Pan-African flower had now bloomed. The RPF was viewed as part of the NRA but under a more focused leadership of the austere-looking disciplinarian Paul Kagame, with none of the shortcomings NRA have so venally displayed once in power.

But perhaps the problem is precisely that many were seeing something that was not really there?

For its part, Kigali eventually made it known that it believes Kampala had already been offering support to a nascent armed rebellion being assembled, it claims, in the forests of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and led by Kayumba Nyamaswa, a former RPF general. This was flatly denied by Uganda’s long-standing Minister of Foreign Affairs (and even longer-standing in-law to the president), Hon. Sam Kuteesa, who said: “Uganda cannot allow its territory to be used to threaten the security of a neighbouring country.”

Given the military role of the government in which Kuteesa serves in changing the governments of the DRC twice, South Sudan (through helping the secession), and of course Rwanda (by which means Paul Kagame became president in the first place), this must be the ultimate demonstration of diplomat-speak.

And given the fact the President Paul Kagame willingly accepted assistance offered by the Ugandan government (in which he was serving at the time) in that interference that led to the collapse of the regime of then Rwandan president Juvenal Habyarimana, perhaps this alleged assistance to his erstwhile General Nyamwasa should not be a cause for surprise, let alone outrage. He will certainly know what may follow.

The rebellion against the regimes of Idi Amin and Milton Obote basically involved arming refugees and exiles, among others, to help wage a war of the government of the country that was hosting them. This was followed by the arming of refugees to invade a neighbouring country, and then arming refugees and ethnic minorities to march against two DRC governments in Kinshasa, where the armies of Uganda, and Kagame’s Rwanda were to work together in driving the armed movement that removed the regime of Marshal Mobutu from the DRC, and backstopped events around the death of Mobutu’s first replacement.

After a lifetime of breaking rules and flouting the procedures and principles of International relations, President Kagame can hardly suddenly expect them to be upheld in respect to his own regime. And especially not by his former accomplice in such conduct.

President Kagame has a long and complex relationship with the Uganda-Rwanda border. At a personal level, he has been responsible for its security and integrity not from one, but both sides, first, as a very senior Ugandan military intelligence officer, and now as President of Rwanda. He has also crossed it in illegal fashion, first as a child in a family seeking refuge, and lastly as a Ugandan-based armed rebel. And now he has shut it down.

Between the countries, the story becomes even more complex. In the last major constitutional revamp, Uganda included a group defined as “Banyarwanda” in the schedule of “tribes” or ethnic groups of the country. This came about for two main reasons: first, there are significant communities of Ugandan citizens in the far southwest of the country that are of the same ethnicities as those found throughout neighbouring Rwanda. This is a common African situation.

President Kagame has a long and complex relationship with the Uganda-Rwanda border. At a personal level, he has been responsible for its security and integrity not from one, but both sides, first, as a very senior Ugandan military intelligence officer, and now as President of Rwanda.

The other reason is that the NRA’s struggle for power did – as the case of President Paul Kagame shows – take on board very many Rwandan refugees (largely of Tutsi origin). These refugees’ initial attempts to obtain Ugandan citizenship after the 1979 fall of General Amin’s government were opposed by many indigenous Ugandan politicians. Despite that (or perhaps as a result of it), they had gone on to swell the ranks of the NRA as it battled the regime of the then President Milton Obote following the stolen 1980 elections. The NRA’s control of full state power on its own standing ushered in the change in their status.

Much as it has enabled Ugandans of Rwandan ethnicity from the Uganda side of the border to stop having to be named after the nearby mountains or to have other labels (sometimes epithets) foisted upon them by their neighbours, this situation only creates further complications for Pan-Africanism, which as yet remain unacknowledged conundrums, but that will be significant in the future.

To complicate matters further, Uganda also has many people of Burundian origin who migrated to the country in the decades following the establishment of the colonial state. How come they have not been recognised as a separate “ethnicity”? More closely, there has been the argument, in the case of the Rwandan “ethnicity”, that perhaps Uganda should have recognised Rwandan Hutus and Rwandan Tutsi as separate groups, as had historically been the case back in Rwanda.

A similar question has been raised about the Asians settled in the country for nearly a century who have made sporadic requests for “tribal” recognition. In their case, will it go back to the Hutu and Tutsi question: will they be labelled the “Asian tribe”, or will they get registered as the various ethnic or caste groups that they identify with in India or Pakistan?

Tribe or nation?

Post-colonial Africa’s historical ideological trajectory has been to insist that all the peoples found within any given set of colonial borders at independence could only be considered as “tribes”, the raw material out of which the new nation would be built. This an extremely deeply entrenched mindset among almost the entire African political class, irrespective of country, and whether in government or in the opposition.

But here’s the thing: In the case of the members of the relatively newly-established Rwandan tribe of Uganda, one only has to cross the border (once re-opened) to morph into a member of a nationality, without a change in ethnicity.

Between the countries, the story becomes even more complex. In the last major constitutional revamp, Uganda included a group defined as “Banyarwanda” in the schedule of “tribes” or ethnic groups of the country.

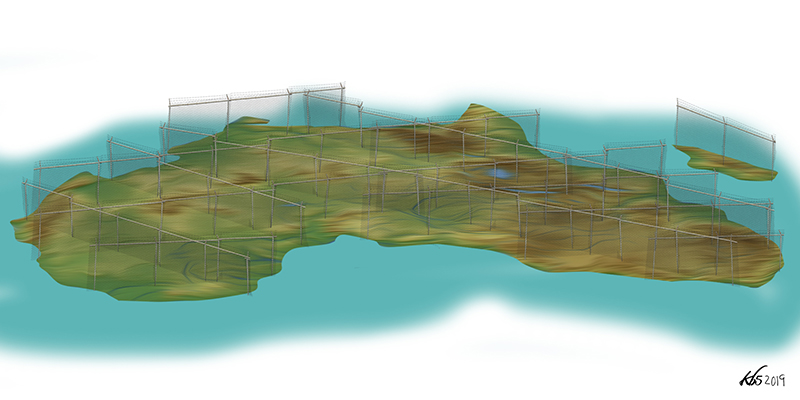

The question arises as to how a European-drawn border developed the magical power to transform the same African ethnicity into either a “tribe” or a “nation”, depending on which side of that border it stood.

Other “tribes” in Uganda, such as (famously, or perhaps infamously) the Baganda, remain trapped. Their pre-colonial status as a nation cannot be as easily re-actualised, as they have no such border they can cross. These designated “tribes” have a dubious status within the given polity. Their rights are ephemeral at best. Their continued existence is viewed with official suspicion, a sort of pre-colonial hangover that must be progressively extinguished, through political means if possible, but by naked force, if necessary. They present in public life often as an abused bargaining tool by members of the petit bourgeois class found among them, as they blackmail those holding state power. “Tribalism” is the destructive political habit that results, and is then used to further stigmatise native identity.

Perhaps Kampala’s problem – evidenced historically by the belittling and patronising attitude towards Kigali since the RPF took power there – is that it cannot shake the thinking that the Kigali regime is little more than a Ugandan “tribe” that happens to control another country. In short, an extension of the attitude it holds towards all the ethnicities within the ambit of its own borders.

All these realities and events strongly suggest that the border is the least of our worries; it is what lies beneath, and before. This is what we shall examine in Parts II and III of this series.